|

|

|

|

| The

Schlinger laboratory studies the activational and organizational

effects of sex steroid hormones on neural structure and function.

Steroids have dramatic effects on brain and behavior in birds and they

are the focus of most of our studies. We are particularly interested in

the process of steroid synthesis: what tissues make steroids that act

on the brain and how steroid synthesis is regulated. Some of this

research is stimulated by the intriguing idea that sex steroids might

be synthesized within the brain itself to influence brain development

or to activate behaviors when birds are reproductively inactive. We

study birds in the lab and in the field, from the behavior and

reproductive physiology of the living bird down to the expression of

genes and the ultrastructural location of proteins in neural and

non-neural cells. Sometimes

the answers we get are quite unexpected and open our eyes to new

endocrine capabilities and unique steroidal functions. Whatever the

outcome, our results enrich our view of the natural world and wonders

of avian biology. Most vertebrates express an enzyme, called aromatase, in parts of the brain, that converts androgens into estrogens. We know that many actions of circulating Testosterone on the brain are due to estrogens that are produced locally in the brain from those androgens in blood. Songbirds express unusually high amounts of aromatase in the brain, especially in areas that might be involved in learning and memory (the hippocampus), auditory processing and song production (telencephalon), in addition to areas involved in reproduction (hypothalamus). At the anatomical level, we are examining which cells express aromatase and where the aromatase protein is found. Some of our current research is stimulated by our hypothesis that aromatase is found within synaptic terminals and elevated estrogen levels in and around the synapse influence pre- and/or post-synaptic physiology. We have studied brain aromatase in several species of wild and captive birds, and even in a unique species of fish (in collaboration with Andrew Bass). |

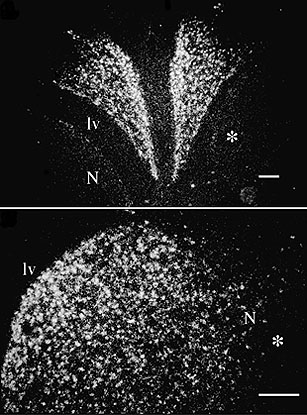

Dark-field microscopy depicting aromatase mRNA expression in the zebra finch hippocampus and neostriatum. Golden-collared manakin

Field work in the Panamanian rainforest

|

|||

Sex steroids are known to be synthesized largely in the gonads, but may be produced to a lesser degree in the adrenals and perhaps also in the brain. All sex steroids are derived from cholesterol, and the class of steroid produced depends on the presence of enzymes that catalyze the conversion of one steroid into another. Steroid synthesis can be studied, therefore, by examining the presence in cells or tissues of the steroidogenic or steroid metabolic enzymes. We use a variety of techniques to look for these enzymes, including by examining gene expression, immunoreactive protein or catabolic activity. We look at the gonads, adrenals and brain. We study the role of steroids a) in brain sexual differentiation by examining steroidogenesis in developing zebra finches; b) in the activation of adult behavior by examining steroidogenesis in zebra finches, non-breeding song sparrows (in collaboration with John Wingfield) and, soon, in a tropical antbird (in collaboration with Michaela Hau). |

||||

The hormonal control of copulatory behaviors have been studies in many species. Many birds species engage in a variety of very complex courtship behaviors to gain access to members of the opposite sex. We know little about the hormonal and neuromuscular control of these behaviors. We are studying the Golden-collared manakin (Manacus vitellinus), a common bird of Panamanian rainforests. Male, but not female, manakins perform an elaborate courtship display that includes loud noises produced by the wings. We have found significant expression of androgen receptors in spinal motoneurons in these birds, including in motoneurons that innervate wing muscles. We have also identified 2 sexually dimorphic wing muscles in these birds. Presumably, androgens act on the muscles and spinal cord to control these courtship behaviors. We believe that these kind of steroid sensitive adaptations may be widespread in birds that perform similar visual and/or acoustic displays. |

||||

|

© 2001-2007 B.A. Schlinger Laboratory, All rights reserved. |